Dr Thomas Mills, Senior Public Health Research Fellow – PHIRST South Bank

If we’re serious about creating healthier places, we need to prioritise health across the planning system – from national policy and corporate strategies, to plan-making to development management. The places we build shape the building blocks of health: housing quality, access to green space, safe active travel, clean air, and affordable healthy food. Yet in many local authorities, health and planning still operate in siloes.

The places we build shape the building blocks of health.

That’s why our recent PHIRST South Bank evaluation focused on a growing workforce solution: hybrid public health–planning roles. We explored how these roles operate across Oxfordshire County Council (working within a two-tier system, alongside five district councils), and in Milton Keynes, Bedford Borough and Central Bedfordshire (served by a shared public health team).

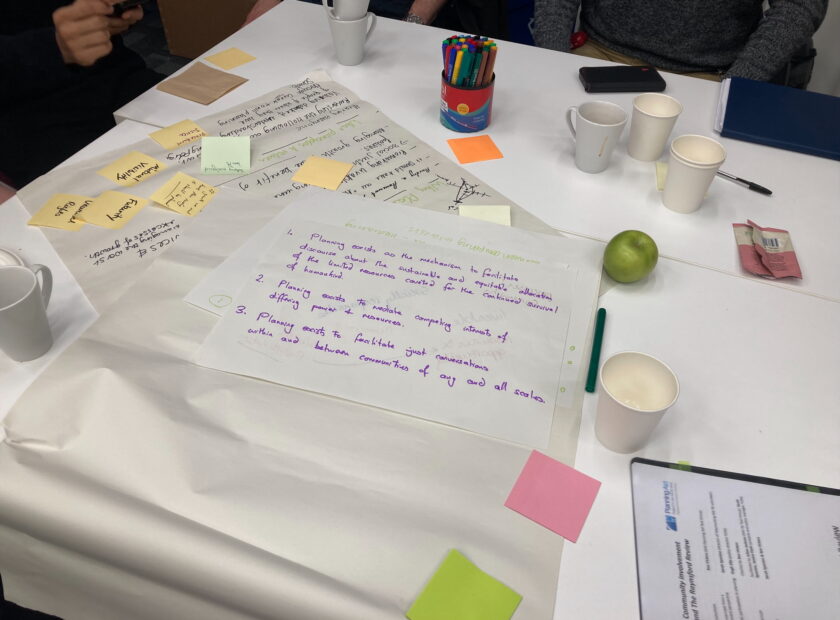

Here, and across the country, a movement of practitioners is emerging – people able to speak both ‘planning’ and ‘public health’ – to drive change locally. Their value lies in how they help planners, often working under extreme pressure, to translate health aspirations into day-to-day decisions (see Figure below for who these roles help).

A movement of practitioners is emerging – people able to speak both ‘planning’ and ‘public health’ – to drive change locally.

Figure: Who do hybrid planning-public health roles help?

We identified five key functions that hybrid posts deliver[1]:

- System leadership – helping reposition health as a strategic priority and creating shared accountability across departments.

- Public health capability building – translating planning systems, timelines and levers so public health colleagues can influence them more effectively.

- Influencing planning policy – embedding evidence and health equity considerations into local plans and policies.

- Enhancing development management – improving scheme design by reviewing applications, strengthening Health Impact Assessments, and shaping decisions earlier, especially at pre-application stage.

- Community engagement and advocacy – amplifying local and particularly marginalised voices, while also supporting inclusive neighbourhood-level healthy placemaking.

Stakeholders described many tangible impacts: improved local plan quality, stronger cross-team collaboration, improved development management processes, and enhanced final schemes – particularly where hybrid teams were brought in early to influence designs.

Importantly, we’re not seeing this in isolation: PHIRST LiLaC has evaluated similar roles in East Sussex and Southampton, building the case for investment[2].

But local government budgets are under sustained pressure. Our evaluation estimated that a full hybrid team – consisting of a fulltime postholder at principal level, and a senior manager with built environment expertise at 0.4 FTE – is less than £100k per year. We considered this as reasonable given the breadth and depth of the impact we observed. But it’s still a big ask when every budget line is contested.

The answer for some local governments might be to optimise what they already have, rather than invest straight away in a full hybrid team. Our five key functions provide a practical guide: someone must deliver them, even if the workforce solution looks different in each place. That might involve exploring part-time posts, or time-limited secondments – embedding planners in public health teams, and vice versa. Or, it might mean strengthening related roles in environmental health, urban design, licensing, transport, highways, housing – each of whom has a vital contribution to make.

However it is organised, the direction of travel is clear: healthier places require expertise that can bridge systems – we all need to work together to deliver health’s building blocks.