The second of two blogs on planning for nature recovery reflects on the gap between the policy rhetoric and the experience of practitioners on the ground

Read the first blog: Has planning for nature got lost in the woods?

Poorly planned urban development has made a significant contribution to the UK’s unenviable status as one of the world’s most nature depleted nations. While evidence as to the outcomes of spatial planning for nature are patchy, existing research does speak to a system failing to secure the most basic safeguards for nature. A recent study by the University of Sheffield shows that housing developments deliver only half of the features promised to support nature on site.

However, the spatial planning system has also been identified by governments across the UK as playing a leading role in planning for, and funding, strategic nature recovery. The devolved nations are pursuing different responses to this challenge but there are some common themes in the approaches taken, including the attempt to monetise the value of nature and a move towards prioritising strategic scale nature recovery.

In England the position is at its most complex, with the recently introduced regime for Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) already under review and with new provisions in the 2025 Planning and Infrastructure Act which will introduce Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs) and the Nature Restoration Fund (NRF).

Planning for Nature

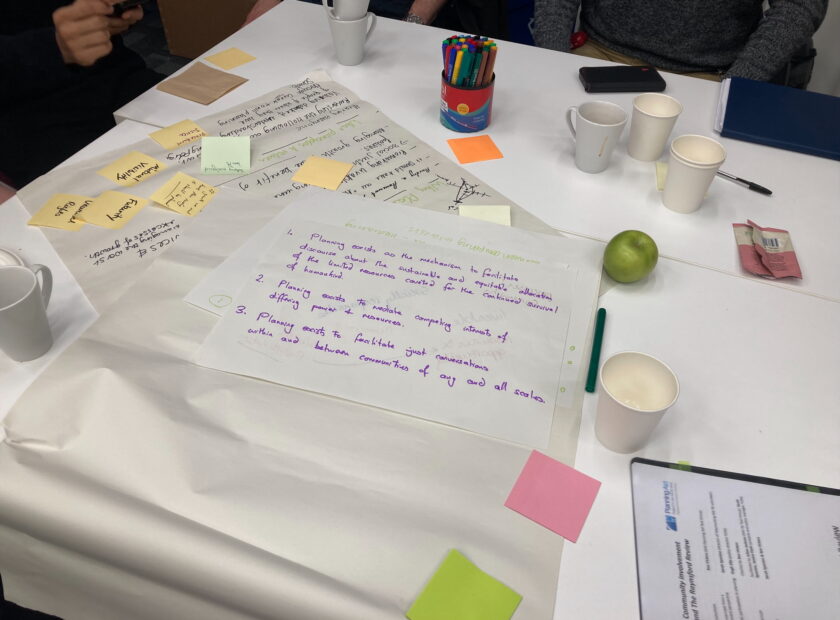

The Planning for Nature Project, led by the University of Sheffield and with support from the TCPA, is beginning to reveal the practical consequences of these new regimes. Through a series of cross-sector focus groups held in autumn 2025 with practitioners and policymakers from England and Scotland, the project sought to take stock of how nature was integrated into the planning systems of each nation. The output of these sessions paints a complex picture of dysfunction which arises from multiple causes.

It has been striking that none of the cross-sector voices thought that the spatial planning system worked effectively for nature. Some participants were willing to defend specific aspects of the system, such as BNG in England, while others pointed to individual outcomes on particular schemes. However, there was a general sense of a system which produced sub-optimal outcomes. The overriding impression from the focus groups was that nature was often an afterthought or a marginal issue in decision making and was consistently rated lower than the drive for GDP growth.

The way we plan for nature recovery can be broadly characterised as institutionally complex, evidence rich, policy heavy but delivery light. Each one of these themes plays out to a greater or lesser degree between Scotland and England. For example, Scottish national planning policy in NPF4 is much more visionary than policy in England but that does not appear to have translated into clearly improved outcomes. There are many contributing factors to this dysfunction but three themes emerged which appeared to be of underlying importance:

Nature as a policy priority

Despite the presence of strong national policy on nature, particularly in Scotland, there was agreement across the focus groups that nature is treated as a peripheral issue in the detail of planning decision making. As one of the participants from a local authority said:

We’ve declared a biodiversity emergency, but at the same time when it comes to the nitty gritty of planning decisions it’s not normally the biodiversity that’s the key point…so I think we’d say, oh yes, we want to support it in the right places, but the right places are definitely not any of the places that we want to build houses.

The prime consideration in planning decisions is GDP growth, reflected in the overarching prioritisation given to factors such as housing numbers. Impacts on nature are mitigated or compensated for, which reflects an underlying philosophy of decision making that trades off nature in favour of growth. This is perhaps a backwards step compared to former approaches to the environment.

Constant policy flux

The focus groups highlighted an interesting paradox that while nature is a secondary issue in decision making it is nonetheless wrapped in a complex web of institutional arrangements, policy objectives and delivery tools. In England, this is reflected in the dysfunctional relationships between the principles of the 2021 Environment Act, the 25-year Environment Plan and Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS), and the functions of the town and country planning system. The dysfunction is not limited to the relationship of different legal regimes but is also evident inside the planning system. Town and country planning not only represents traditional biodiversity protections but new and highly complex tools such as BNG, Environmental Outcomes Reports (EORs) and the soon to be introduced EDPs and NRF.

It was a striking feature of the focus groups in England that practitioners felt bewildered and ill equipped to handle the demands of the ever-shifting policy and legislative landscape, nor understood how new mechanisms will operate in the context of severe skills and capacity shortages.

As somebody who’s focused on those kind of environmental elements of it, I find it incredibly hard to keep up with all of the change that that’s going on. And I can only imagine how difficult it must be for colleagues that are in a direct planning role who have to not only consider the environmental aspects, but all of the other areas that are also going through (change).

Focus group participant

There is no sense of how these differing legal regimes and institutional owners can amount to a coherent framework for nature recovery – measures were being tacked onto existing planning processes with little regard for how they might operate and interact in practice. As one participant noted:

The legislation very, very rarely deals with the actual outcomes. It just deals with all the process and it’s very, very process heavy.

Putting a Price on Nature

In our first blog, we highlighted the tension between securing local biodiversity gains and strategic offsetting that was a key theme of the focus groups. The shift towards the latter approach is reliant on putting a price on nature.

There was some resistance to the idea of monetisation and offsetting in Scotland where a long-promised biodiversity metric has not yet been introduced. In England BNG, EDPs and the Nature Recovery Levy all depend on being able to monetise the value of nature and then create opportunities to mitigate or offset those impacts. Participants had various views on this approach but most acknowledged that this raises thorny issues. This includes the value being placed on different kinds of nature, concerns about whether developers are being offered the option to pay to pollute, and important questions about who benefits from subsequent investment in nature recovery, especially if it is delivered offsite and potentially a long way from what is being lost to new development.

Some participants also raised an additional question as to whether it is logical for developers to pay for strategic nature restoration, particularly when such funds may reduce the amount of other public goods, in particular the level of affordable housing.

While there is only space in these blogs to give a brief flavour of the challenges of how we plan for nature recovery which emerged from the focus groups, it is clear that there are systemic problems which need to be addressed.

Moving backwards?

It is interesting to reflect that we have moved, particularly in England, back to a trade-off approach that dominated planning decision making until the introduction of sustainable development as a priority objective in 1987. The sustainable development paradigm was focused on achieving simultaneous progress on social, environmental and economic goals holistically. Where such outcomes could not be achieved, developments should not proceed. It is significant that sustainable development as a concept did not feature in the discussions with practitioners, which raises important questions about the philosophy of how we plan for nature. ’

Instead, discussions revealed how nature is being managed on an increasingly transactional basis. Whilst BNG in England has given legislative weight and stoked cultural change in how planning delivers for nature, the way that practitioners on the whole spoke about nature as a ‘problem’ reveals that it is regarded in terms of an additional burden on development, reducing nature as a cost to minimise alongside other policy asks (such as affordable housing).

This also puts hard fought policy gains at risk as they can be argued against on ground of cost – as has been seen in the recent announcement to exempt small sites from BNG. This approach also devalues and undermines efforts to understand nature in a more integrative way, and to imagine a more regenerative approach to development that supports nature recovery as an essential basis for human life.

Perhaps no one should be surprised that a legally and institutionally complex system which is chronically under resourced, and is regarded at best as a nuisance by HM Treasury, is failing and will go on failing. Only when nature recovery is seen as the foundation of our economy and our personal wellbeing will we be in a position to frame a new environmental planning system which delivers both effective and fair outcomes.

You can find out more about the Planning for Nature project here: https://www.planningfornature.org/

Header image: A housing development in Wantage, Oxfordshire. (Credit: R Callway 2025)