To ensure better and more inclusive health outcomes, the TCPA has identified 12 Healthy Homes Principles that all new housing developments must provide. Each month, this blog series explores one of the Principles.

Healthy Homes Principle: Limit light and noise pollution

Each year the equivalent of 130,000 healthy life years are lost due to noise pollution for people living in England. Sleep disturbance alone costs society an estimated £34 billion annually (UK Health Security Agency, 2023). Despite these alarming figures, both noise and light pollution remain poorly understood and inadequately regulated, even as evidence grows about their serious health consequences.

Noise pollution, defined by the European Environment Agency as ‘harmful or unwanted sounds in the environment’, comes from sources like road traffic, aircraft, industry, and leisure activities (House of Lords Library, 2024). It has been identified by the World Health Organization as the second largest environmental cause of health problems after air pollution.

The negative health effects of light pollution are often overlooked but are similarly concerning (TCPA, 2024). Light pollution is thought to impact health by disrupting circadian rhythms and sleep. Light pollution has been increasing in recent years but research about the impacts on health is limited.

Light pollution is thought to impact health by disrupting circadian rhythms and sleep.

Both noise and light pollution contribute to a range of adverse outcomes for people, including heart disease and premature death (Science and Technology Committee, 2023). The unequal exposure to noise and artificial light in more deprived areas is also a concern, contributing to further increasing health inequalities (Tonne et al, 2018). Yet, in both policy and public discourse, little consideration is given to how our homes can be planned, designed, built and managed to cut exposure.

This latest blog in our Healthy Homes series explores the hidden impacts of noise and light pollution on health, and why they need to be addressed in housing provision.

The health impact of noise pollution

Noise pollution is a widespread yet under-recognised public health issue. This is despite widely reported health impacts, including chronic annoyance, sleep disturbance, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, depression, anxiety, and reduced cognitive performance, particularly in children (TCPA, 2024).

All too often, noise is seen merely as a nuisance rather than a hazard to health.

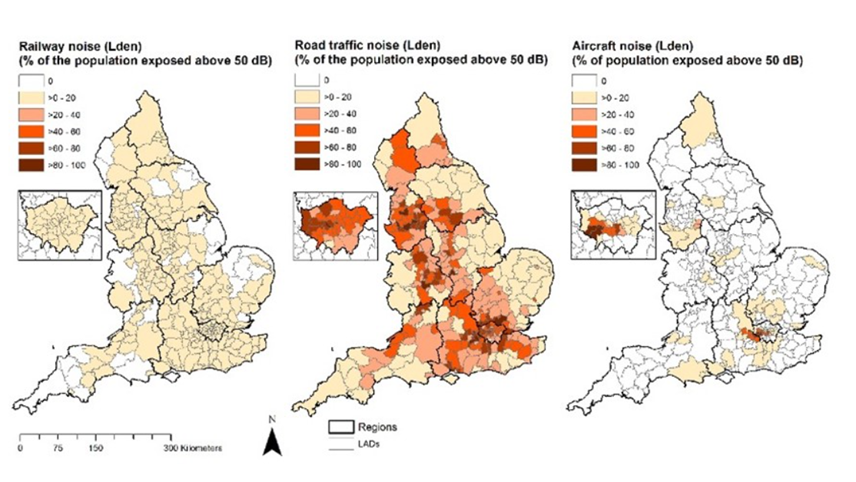

In England, nearly 40% of adults are exposed to long-term road traffic noise above 50 decibels, a level associated with negative health outcomes (UK Health Security Agency, 2023). Yet all too often noise is seen merely as a nuisance rather than a hazard to health. While individual risk from noise exposure may be small, the cumulative effect across millions of people creates a significant health burden (House of Lords Library, 2024).

Credit: UK Healthy Security Agency, 2023

Poor quality, high-density housing is particularly at risk of unwanted noise exposure. Thin walls, reduced space, and close proximity to neighbours can lead to a sense of intrusion and overall invasion of privacy. Such noise disturbance has been found to worsen stress and diminish overall quality of life.

Renters are especially affected by noise pollution, reporting more frequent disruption and discomfort than residents in other tenures.

Renters are especially affected, reporting more frequent disruption and discomfort than residents in other tenures (Lindsay et al., 2010). Disparities in noise exposure are also linked to housing location. For example, a London-based study found Asian residents were more exposed to traffic noise than white individuals, as they were more likely to live near busy roads (Tonne et al, 2018).

To address noise pollution, acoustic considerations need to be better integrated into urban planning and residential design. The challenge is balancing efficient land use with the need for a peaceful, private living environment. Other interventions, such as quieter vehicles, active travel promotion, and better flight path planning have also been recommended (UK Health Security Agency, 2023).

The challenge is balancing efficient land use with the need for a peaceful, private living environment.

Linking light pollution and ill-health

Artificial light at night (ALAN) has become a defining feature of modern life, illuminating streets, homes, workplaces, and public spaces long after sunset (Candolin & Filippini, 2025). While lighting can improve safety and productivity, overuse is increasingly disrupting natural cycles, harming both human health and the wider natural world (CPRE 2016). Artificial lighting interferes with the body’s circadian system, which governs sleep, hormone production, mood and other essential biological functions (Science and Technology Committee, 2023; TCPA, 2024).

While lighting can improve safety and productivity, overuse is increasingly disrupting natural cycles.

Exposure to ALAN is linked to higher risks of chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (Thompson et al., 2022). Concerningly, epidemiological studies have identified associations between ALAN and certain cancers, including breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer (Candolin & Filippini, 2025).

Despite these findings, light pollution remains a poorly understood and under-researched issue. The Science and Technology Committee has called for greater investment in studies to better define exposure levels, quantify impacts on sleep and health, and evaluate the effectiveness of mitigation strategies (Science and Technology Committee, 2023). A deeper understanding of the consequences of exposure to artificial lighting is essential to protect both human wellbeing and ecological balance.

Credit: fr.wikipedia.org

Noise and light pollution in permitted development housing

When commercial buildings are converted to residential use through permitted development rights (PDR), regulation of noise and light pollution is limited and inconsistent.

Under PDR rules, noise pollution receives slightly more attention. Building Regulations Approved Document E on sound proofing, can apply to some PDR conversions, depending on the building’s prior use class. Similarly, prior approval conditions for developers to undertake a noise assessment only applies to certain previous use classes of building – for example, office-to-residential conversions (Class O) do not need to apply a noise assessment. There is also no current policy requiring consideration of the proximity of PDR housing to sources of noise, such as major roads or industrial activity when approving schemes (TCPA, 2024).

There is no current policy requiring consideration of the proximity of PDR housing to sources of noise, such as major roads or industrial activity.

Regarding light pollution, government guidance recognises the planning system’s role in limiting exposure to artificial light, but there are no enforceable requirements for PDR housing which happens outside the full planning application process. Local authorities can act on lighting that constitutes a ‘statutory nuisance’ under the Clean Neighbourhoods and Environment Act 2005, but this only applies to certain types of light pollution – e.g. railway, airports, goods vehicle operating centres are not included (TCPA, 2024; DEFRA, 2015).

Planning and designing with noise and light in mind

There are various examples of Local Plan policies that set clear housing development and design standards to cut noise and light pollution, such as Epping Forest District council’s Policy DM9 High Quality Design. This and other examples are referenced in the Planning for Healthy Places guide produced by the TCPA with the TRUUD research programme.

Design codes are an important soft tool in tackling these issues, providing a practical framework and criteria that aim to embed health creation and reduce health inequalities. Codes can specifically address noise and light pollution through careful planning of built form, land use, and building layout. For example, measures include separating noise-sensitive and noise-generating areas, using enhanced sound insulation, and employing natural screening. The location and orientation of different activities and buildings can help further mitigate environmental impacts. Applying these principles early in the design process, codes can contribute to ensuring healthier, more liveable places, before development proposals even reach the planning application stage (Quality of Life Foundation et al, 2025).

Design codes can specifically address noise and light pollution through careful planning of built form, land use, and building layout.

The Institute of Lighting Professionals (ILP) also provides free guidance regarding exterior lighting, regarding cutting light intrusion and glare, as well as to promote security without impacting nocturnal wildlife, such as owls and bats (ILP resources).

Building homes that limit intrusive noise and light pollution all-year-round, is a central Healthy Homes Principle in the Campaign for Healthy Homes. To promote thriving healthy and inclusive communities, a fundamentally different approach to delivering new homes is required – one that puts the quality and affordability of new homes and communities as highly as the quantity that are delivered.

Clémence Dye and Rosalie Callway