To ensure better and more inclusive health outcomes, the TCPA has identified 12 Healthy Homes Principles that all new housing developments must provide. Each month, this blog series explores one of the principles

Healthy Homes Principle: Liveable space

The 2020 global pandemic underscored the need for homes that support both daily activities and overall wellbeing. During the Covid-19 lockdown, nearly a third of British adults—approximately 15.9 million people—reported mental or physical health issues linked to inadequate living space (National Housing Federation, 2020).

Providing housing with sufficient liveable space needs to be prioritised. Yet, in England, 850,000 households live in overcrowded conditions (Resolution Foundation, 2024). More than two million children have little to no personal space, and 300,000 share beds with family members (National Housing Federation, 2023). The space provisions for children are very poor – Part X of the Housing Act 1985 means a child below the age of one is disregarded and a child between the age of one and ten counts as a half person (UK Parliament, 2023).

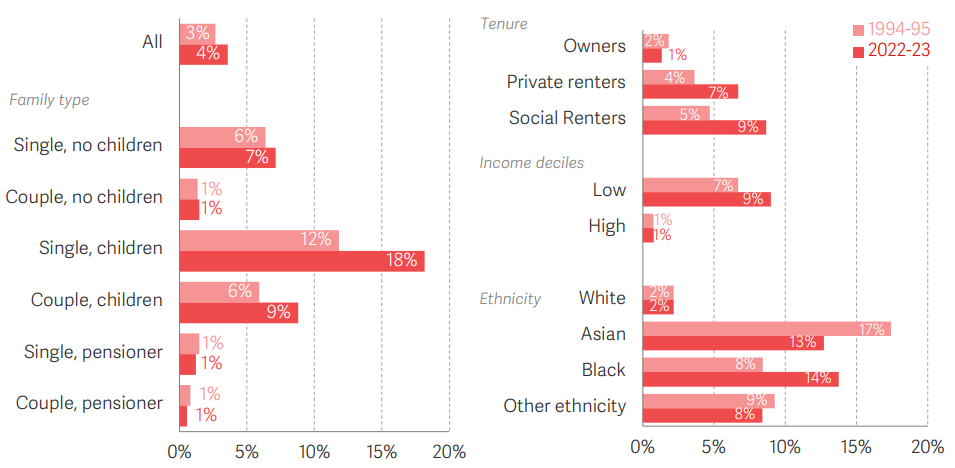

The issue of liveable space also highlights existing inequalities. Overcrowding is more prevalent among social renters (9%) compared to private renters (7%) and owner-occupiers (2%). Households from black and ethnic backgrounds are three times more likely to experience overcrowding than white households (TCPA, 2024). The figure below illustrates how overcrowding varies by family type, tenure, income deciles, and ethnicity, revealing that many are living in overcrowded homes at rates not seen in the last three decades (Resolution Foundation, 2024). These numbers emphasise the urgent need to ensure that all homes provide, at a minimum, adequate liveable and storage space.

Source: Resolution Foundation Housing Outlook Q2 2024

The health impacts of lack of space and overcrowding

Overcrowding in houses with multiple occupants poses significant health risks, exacerbated by weakly enforced space standards in the UK housing system (TCPA, 2024). The country’s housing stock is characterised by relatively small dwellings, with the average size 32% below that of the largest homes in Europe, which are in Luxembourg. This situation is further complicated by ‘hidden overcrowding’, where overcrowded households do not meet the statutory definition due to loopholes, such as no limits on same-sex occupants sharing a room or kitchens of a certain size being deemed suitable for sleeping (A. Kearns, 2022).

Evidence indicates that the consequences of overcrowding or insufficient space include an increased transmission of infectious diseases, particularly respiratory and digestive illnesses; psychological distress, manifesting as depression in women and aggression in men; and lower educational attainment, particularly impacting secondary school students. Overall, the lack of adequate space standards and the prevalence of overcrowding significantly undermine health and wellbeing in affected households (A. Kearns, 2022).

Living in unhealthy places – TRUUD film

This film, produced by TRUUD, an academic research consortium which is providing new evidence to inform health-promoting decision-making in urban development, is a powerful account of the multiple ways that poor space provision can impact on a person’s physical, mental, and emotional health and wellbeing. It captures a family’s experiences of how it feels to be living with overcrowding.

‘If they lived in other conditions, in a less crowded home, everybody would have a very different life and very different health outcomes. With children, it kind of flags it as a life course issue about what kind of start it is giving to those young people for the rest of their lives, in terms of the effects on their education, their behaviour, their sleep. That’s going to impact their health into the future.’ Dr Jo White, University of West of England, TRUUD researcher, public involvement team.

Legislation and deregulation under Permitted Development Rights

While legislation exists, England does not have a legal requirement to ensure sufficient minimum space in homes. The statutory Overcrowding Standard in the Housing Act 1985 sets minimum standards that are inadequate and fail to account for children under one, while children under ten are considered to require the space of half a person (TCPA, 2024).

The Nationally Described Space Standard (NDSS) established a voluntary minimum dwelling size of 37 square meters. However, local authorities can choose whether to apply this standard, meaning new developments created through planning applications do not legally have to comply, except for London Boroughs under the London Plan. As of 2021, homes created through Permitted Development (PD) are required to meet this standard, but many prior PD conversions are exempt (TCPA, 2024).

A tiny ground-floor bedroom in a converted office, where three young children slept with no room for a cupboard, exposed to damp, poor insultation, and noisy neighbours. Templemeads House – Harlow (photo credit: Rosalie Callway).

Licensing requirements for Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs – under the Housing Act 2004) with five or more non-related occupants is another regulatory tool to address overcrowding. Nonetheless, local authorities do not consistently apply HMOs to PD conversions, as such properties can often involve mixed tenures (with both private rental and temporary accommodation). In 2017, the government reviewed the NDSS and set minimum bedroom sizes for HMOs: 4.64 m² for one child under ten, 6.51 m² for one person over ten, and 10.22 m² for two persons over ten (A. Kearns, 2022). These sizes remain insufficient to ensure the health and wellbeing of residents. Ultimately, without robust enforcement of space standards, many individuals and families will continue to suffer from the negative impacts of cramped conditions and overcrowding.

In the longer term, more large family homes are needed to help tackle overcrowding, especially in the social rented sector. Ensuring all new homes have, as a minimum, the liveable space required to meet the needs of people over their lifetime, is one of the 12 core principles of the Campaign for Healthy Homes.