The TCPA’s Director of Policy Hugh Ellis reflects on how best to reform the planning system – and which mistakes to avoid

As we count down to the next general election there is an increasing frenzy of organisations producing advice on how to reform the planning system. New initiatives are being established to review housing delivery and opposition politicians are being bombarded with a revolving door of often conflicting advice. Some of this advice is sound and sensible but a great deal reflects the corporate needs of particular sectors rather than the overall public interest in an effective and democratic planning system.

We should all be clear that the main questions which surround planning reform have all been asked and answered in the various reviews of the system over the last decade. The Raynsford Review provided the foundations for an effective and legitimate system, Oliver Letwin dealt with strategic delivery issues, the RTPI with the funding crisis, and the Committee on Climate Change has repeatedly set out the preconditions for an effective planned response to the climate crisis. There is no mystery to discover about what’s wrong with the current system nor how to fix it.

The issue for planning reform is not technical but ideological. Planning is obviously the rational solution to an age defined by crisis. But for those who are committed to the Nirvana of the free-market, planning is not a set of practical tools for our collective progress but a totemic expression of the democratic state and therefore intrinsically bad. No amount of evidence can shift this conviction.

The result of the intense reform which has been driven by the tension between the ideological and the practical is a planning system which is now highly complex but also desperately ineffective. Underfunded, demoralised, and lacking public trust, the system is clearly on its knees. And that matters enormously because the planning system is central to any government who has ambitions for an efficient and democratic system producing healthy and climate resilient communities.

Ultimately it will be the first 100 days of the next government which will shape the direction of the English planning system. When ministers come to make their judgments about how that system should be framed, they should bear in mind six obvious mistakes of past reform.

- Define the problem you are trying to solve.

We have wasted enormous amounts of time and resource in creating and then abolishing different forms of strategic planning, differing shapes and structures of the development plan, endless failed attempts at infrastructure levies. What has all this been designed to achieve?

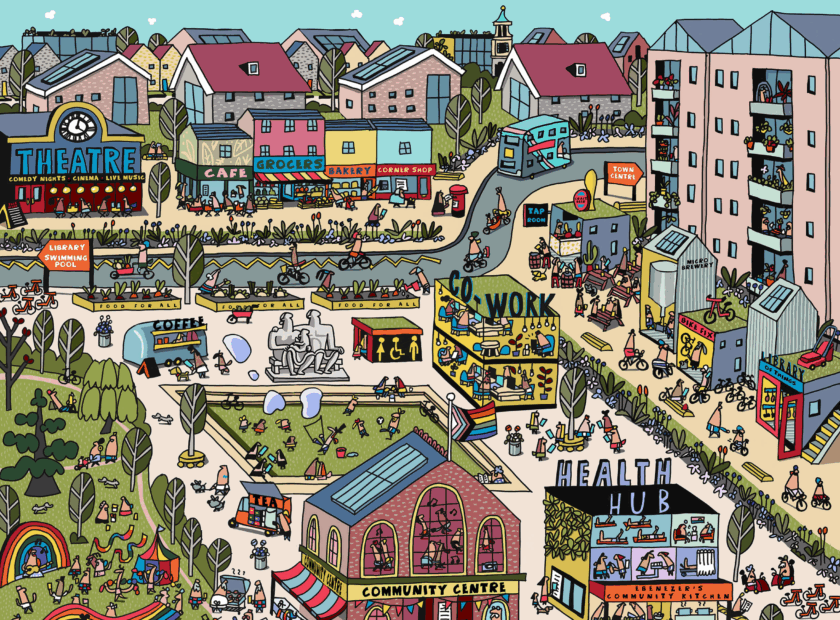

The first priority for the next government on planning reform is to make sure it asks the right exam question. Is planning simply about the creation of consents for housing or is it concerned with the much more complex task of delivering homes and communities which are designed to be resilient to the climate, housing and health crisis? In carrying out this complex task, are people to be given a voice in the future of their own communities? Do not embark on planning reform unless you can clearly answer these foundational questions.

2. Don’t confuse hearsay with evidence.

Planning reform has been based on mythology about the performance of the system, not on verifiable evidence. This mythology is driven by hearsay where in almost every key meeting about planning reform someone has a story about a ‘delay’ that they have personally encountered.

These frustrations may be real, but the causes are always complex and require detailed and rigorous data. Very often they are about vital transport or flood defence infrastructure investment, over which local plans have marginal or no control.

As a result, planning reform begins by assuming that planning is a problem to which the answer is deregulation. This very effectively diverts attention from the actions of other players including the private sector. This lazy approach to planning reform produces perverse outcomes including the obvious failure to ask how planning can be a solution to coordinating and ultimately de-risking development.

3. It’s delivery that counts.

Planning reform always ignores questions of housing delivery. Since 1980 local planning authorities have not delivered homes at any scale in England. They have however consistently consented more than 300,000 homes a year – exceeding the government’s national target for housing. The private sector is responsible for the delivery of the vast majority of these homes. The evidence is clear that the private sector has no financial interest in delivering at a rate which supports the government’s target.

It is curious then that reforms are continually focused on the planning consent process while none have been focused on reforming the private sector’s business model. Planning can of course play a major role in delivery by creating a framework for coordinating infrastructure and investment and, most important of all, by de-risking development by acting as a master developer through mechanisms such as development corporations. There is no mystery as to how to deliver homes, there is simply no political will to get the job done.

4. People must not be an afterthought.

Planning reform always fatally underplays the need to build public legitimacy in the system. Endless papers on reforming the structure of planning always deal with public consent as an afterthought, as if it can be bolted on once the structures of planning have been agreed. This ignores the fact that previous sensible approaches to strategic planning were all brought down because of a failure to deal with public legitimacy. This created the national political space to abolish structures which were technically and practically important to sustainable development but disconnected from people’s lived experience.

Ministers almost always underestimate the power of local communities to resist development if they feel locked out of decision-making. We cannot build without consent and rebuilding trust requires a serious approach to citizens’ rights, meaningful devolution of power to the community level, and a new culture of trust inside Whitehall that goes way beyond digital gimmicks.

5. Beware the chaos of local Government boundaries.

Despite significant centralisation, many planning functions remain a core part of local government. You cannot embark on a coherent strategic planning framework without a parallel process of effective and strategic boundaries for local government. The structure of local government in England is a chaotic mess and the raft of bespoke devolution deals has made this position much worse. A clear example of this is the failure to give strategic planning powers to the latest round of devolution settlements.

6. Pay attention to the soft stuff.

Planning reform has been consistently organised in an Alice in Wonderland world where changing law and regulation is expected to make a practical difference on the ground. This ignores the fact that the public planning service is on its knees with a crisis of morale and capacity. A great deal of that crisis has been generated by ministers consistently denigrating the practise of town planning, but it will take more than supportive speeches to deal with these soft cultural issues.

Local government will have to be properly resourced, and the skills and outlook of planners will need to be refreshed and refocused to deal with the pressing issues of the climate crisis and to allow time for meaningful conversations with local communities.

To some extent, these six mistakes have defined the last 40 years of planning reform, but one error is particularly new.

Over the last 14 years, national government has paid no attention to building consensus amongst the various diverse players in the planning sector. Cross-sector sounding boards have been abolished and bilateral negotiations have become the norm. This has had the beneficial effect of shielding ministers from professional advice which may be critical of their agenda, but it poses more serious problems for the future of reform. Forty years ago, the various sectors shared some core assumptions and values about planning. They may not have like the implications, but they could, to some degree, coexist.

Future reform cannot work without public consent, but it will also fail if it receives the outright hostility of key players. We have to get back inside the tent with each other and be subjected to the discipline of understanding what appears, at first glance, to be irreconcilable differences. We must do this because of the overwhelming public interest in a system which can secure our collective future, a system which must simultaneously build homes, tackle the climate crisis, restore nature, and secure our long-term health and wellbeing.